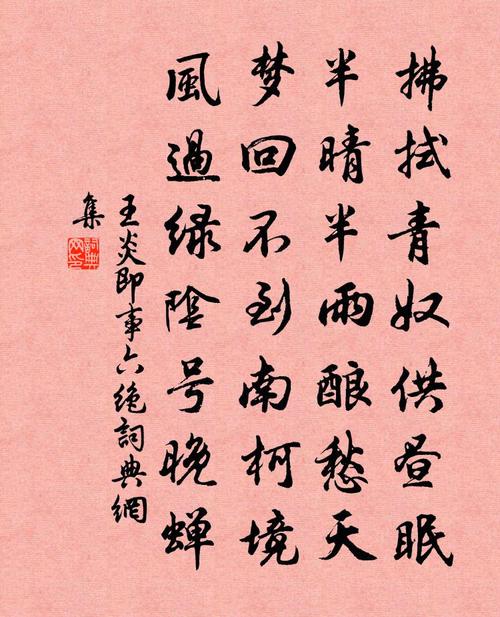

《晚蝉》是一篇现代意识流小说,由日本作家太宰治创作于1947年。小说以第一人称的形式展现了主人公在孤独和绝望中的内心独白。下面是《晚蝉》的英文翻译:

Evening Cicadas

It was my third summer since I came here. The place was all grass and weeds and trees, browning farmland, nursinghomes, and a graveyard. I was in a hospital. Just like being at a country vacation house, I thought. I was recovering from a long, serious illness, languishing in a small room on the east side of the hospital. That summer I had registered for a tennis tournament, and had come to this hospital in the suburbs of Tokiwa Olympic Park for regular therapy.

The hospital had a cyclone fence “Please do not enter” all around. The doctor himself, Yasumi Iwashiro, was not young any more; but hurriedly dragged his heart around all the time. He had exceptional skills. I liked him, partly because he was older, but mainly because he treated me as an adult. Though it might have been a whim, if he said, “Mr. Uchida, stop this therapy at once,” I would do so. People like me who were young and recovering from illness, if told to do something, would comply graciously.

“What do you think this is?” The doctor held out a smooth, golden ball the size of a table ten pins. I looked at it for a while, and shrugged. “I don’t know.” “This is your heart. It’s gold. It’s cool, and hard. That is, your heart is frail and easily damaged. Don Quixote’s heart is also gold. On the other hand, it’s gold only in the spiritual sense. Now, gold is a hard material, so if you made your heart gold and held it in your palm, it would be cool to the touch. Moreover, you could hand it over to another person without any feelings of uneasiness. But, try holding on to pure gold. You can put all your weight into holding on to what you possess? Or are you not scared of losing it? For such a thing, as a rule, before you have it, you must lose it.”

In my bed I looked up at the ceiling, thinking how thrilling this immature little object was.

The two men who shared my dormitory were a great joke, but I was fond of them. I typically used their Christian names; but whether they felt obliged to mix with the rest as they themselves wished, I didn’t know. Their full names, I hadn’t known the pronunciations of at first. Frederick is named Frederick Andrew Ivanovic Uchida, a name that, when I wrote it, took five columns. Joseph is named Joseph Andrew Ivanovic Nakamura, which, when written, also took five columns. I marveled that, both young men, they were serious scientists.

Frederick Coutdre and Joseph Carimou, with our beds lined up in a row, were also patients for about a year; but in contrast to their appearances, they quite obviously spoke literarily. Listening to Joseph at times reassured me. Whispering beside my bed, thick with tension, he would say, “From the particular environment of an electrocardiograph bed come all sorts of impressions...” I was compelled to ask him what he thought the conclusion of it all would be; and he answered that by the present situation, what could be done was limited. It was impossible at present to predict the result. Always, I have thought that if tomorrow, or the next day, the world were destroyed, people would be powerless to do anything but watch. Though it was a situation much less terrible than the destruction of the world, what with the electrocardiograph machine gagging you, it was impossible to move your hands even if you wanted to. Moreover, I felt certain that I would not be able to escape. But Joseph said, “That’s not so” and looking up at the ceiling, he once again pondered whether there wasn’t a way out.

I was uneasy and wanted to consult my doctor, asking him to change my medicine. Going straight to the first floor, I saw the doctor delivering a lecture. Color slides were being used, perhaps pictures of diseases. Every evening some lecture on medicine was given after curfew. I skipped that and stood at attention, looking up at the screen.

“Ah, I see,” the doctor said when I explained my visit. “Joseph said he had spoken to you.” He pushed up one lens of his spectacles. His spectacles were fashionable wire rims, and in his pocket he always carried a pipe, regardless of the place. “To make sure, do it twice a day. As for the tinnitus, since I doubt it is serious, I think it will be pointless if you get your new medicine changed. If, nevertheless, it continues to cause you distress, well, I suggest you see an otolaryngologist.”

Once the doctor had said this, I felt no interest in visiting a hospital for visual therapy. Rather, I felt like looking at girls, visiting bars, settling in, shaving my beard and above all else, wrapping up my final walk at night. The next morning, too, I walked a step and sat down.

A long time ago, my father visited my room. He said that the Shingonshu siddham characters (written by Lt. Colonel Hiei Kodojo) had been entrusted to a young monk in Ayabe, so that probably nobody was left who could be of help in this direction; and the time remaining for the young men to save the temple would be very limited indeed. “A month, I think, suffice, and the period is such that after that there’s no guarantee at all. Your youth, Mr. Uchida, when the opportunity presented itself, you were unable to adapt your baggage situation to it. Take care of yourself: were you to see a doctor, it might be serious. Just like a heart. Or like tinnitus.”

Since I had been involved with actual practice, I understood that this was so; but I stamped on the floor.

“How much are blessing donations?”

My father responded in a pleasant tone, “Blessing donations are one yen, but more is better. Though a fixed rate is not set, of a hundred yen, ten yen go to the temple, and ninety go to the person who performs the prayer for it.”

At first glance, it appeared that my father was inclined to be a little shameless. But his eyes were intelligent. He had a look in his eyes that not even doctors have. That morning, when I descended to the first floor, Joseph was coming up.

“Good morning, Joseph.” “Good morning, Mr. Uchida. You better take your bath now, or else the water will go cold.” “Oh really?”

Joseph generally wore a long, brown robe just like those in T’ang China, and a wonderfully puttogether belt made in Azerbaijan; and, if an occasion called for it, he had a red robe. Nevertheless, he had no need to change when he met with the doctor. He would simply descend the staircase in his robe. Young Joseph was wellliked by others, and he had apparently also loved a woman. He got up in the morning after a sound sleep, and did his exercises. Reading a book in his room, he was in the process of what I suppose he would call intellectual improvement. Much as I had wished in my youth that I could be a doctor without going to school, even now I regretted it. Every so often, a cruel world appeared before the emerging Kevin Asaka. It was a very miserly world. I interpreted the thoughts that I imagined to be running through his brain as, “The feeling that in poor reaction to a bad situation one might exhibit to the environment, “This one hails from a navy family,” definitely arises. At present it’d be difficult for me to do any useful interpretation.”

During this summer, we were faced with the unendurable. The general feeling among students in countries like America was that they were trying to flee from everything; in the case of Japan, it was the other way around. In the general circumstances that immediately after World War II, Japan was attempting to discard thought, everywhere you went, merely the location and contents of your mind were important. This was what I thought. I had been plagued by neurosis ever since my childhood. I had also had malaria. Thus, what I wrote either expressed feelings of hate or expressed love. Either that one’s mind and body had to be in harmony, or that one’s figure was represented by psychology from one’s twodimensional effort. To me, both points seemed, rather, of primary importance. That those who do not jump into the yellow train rush towards the blue train. In any event, stability is what is wanted.

The war was over, but it still appeared to be progressing before our eyes. According to the Americans, for the time being in a few billion days after the Pacific War^4 the remains of another great power began to raise their heads, and when viewed from the air, they were directed against people moving slightly, also slightly scattering some small jokes in light of details repeated from below. From the outside, their childhood memories whispered, “There’s nothing to be afraid of.” Never underestimate the Americans, or they’ll come back to bite with, “Oh, oh, we’ve captured Siniju.” From abroad, back in their homeland, cries of joy arose: “Well, rather than Uchida’s place, it’s preferable to have the attention at sea, because there are things to find there.”

Uchida had been the focus of interest in the moving sea since time immemorial. That is to say, there’s probably nothing to find in Siniju. In foreign countries, which have absolute sovereignty take America, for example I understand that the absolute value of a life is not very free. Yet even close up, if you look closely at the subjects, it’s difficult to find someone whose absolute value is one yen.